5 Ways to Break Out

How factory schools have trapped us — and how to bust out

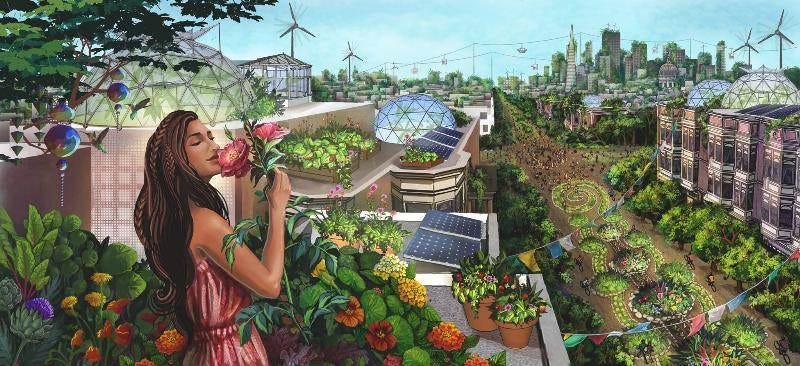

I believe in a reasonably optimistic future. A solarpunk future. Solarpunk is a movement that imagines how adapting to climate change might actually lead to better societies. It’s not necessarily utopian, but it’s a welcome change from the dystopian stories that are common right now. The word solarpunk blends one symbolic technology — solar power — with the counter-culture punk spirit needed to reinvent ourselves. I can’t get enough of it.

But if our schools are to be generators of the future, which is one way to see their purpose, then we have some work to do to bring about this solarpunk vision. That’s because right now, our schools are essentially factories. Modern mass schooling was explicitly designed, in the late 19th century, around the cutting-edge organizational model of the day: a factory. Crazily enough, steel mills were a particular inspiration.

That era’s famous management gurus, like Frederick Taylor, extolled the virtues of being able to measure every step of steel production down to the second, and based on that, to extract maximum productivity from each worker. Their ideas directly inspired the design of early mass schools, which proudly created the story that all students could learn the same thing, at the same pace, in the same way. Well, all “normal” students that is — they had to invent the idea of a normal student in the process — and everyone who didn’t learn according to this “one way or else” approach was declared abnormal. Oops, there goes the majority of the population.

It's hard to believe, but nearly 150 years later, this mindset is still how most schools operate. We expect students to all behave the same and come out more or less the same. We punish or pathologize those who don’t. Let me cut to the chase because so many have already made this argument: this factory model never worked well, it holds us back from accessing much of our human potential, and the simplistic linear thinking it teaches has landed us in situations like the climate crisis.

And that’s enough of bashing the past, because what I’m most interested in talking about is how we step toward this solarpunk future. We know how. We can do this. Here are five ways to evolve how we educate…

1. To understand people, use developmental maps.

Until we have new ways of understanding human potential, we’ll be (a) often confused and frustrated by what kids do, and (b) tempted to default back to testing their memorized content when we can’t think of any better way to measure their progress. We need something better. I think maps of human development are a good answer.

Just as parents of newborns and toddlers would be baffled all the time if no one told them about the developmental stages their child is going through, so too, parents and educators of older kids — especially adolescents — will be baffled and lost unless they have a developmental map to guide their way.

What does this look like? In my book I talk about three developmental stages that apply to early adolescents, each defined by their core drive — belonging, achievement, and authenticity. You can map all kinds of development — cognitive, emotional, ethical and more — to these core stages. Knowing someone’s developmental stage tells you how to reach them, what challenge they’re working on, and why they act the way they do. Here’s one developmental map I made from several research sources (visualized by the amazing Stephanie Kinkel), showing how adolescents grow like a tree does, from the inner ring of wanting belonging above all else, to the second ring of seeking to achieve, to the outer ring of becoming capable of being authentically themselves:

2. See beyond “brains on a stick.”

The late great Sir Ken Robinson famously described the way schools see students as “brains on a stick” — no body, no family, no history, no social web — just a brain in front of you, awaiting the teacher’s delivery of knowledge. Well, that’s a recipe for frustration if ever there was one! One way out of the factory model is to see us instead as embodied, emotional, and social beings.

When we understand that we are embodied, we begin realizing what Dr. Mona Delahooke has said so well in her writing — we over-estimate how many of young people’s decisions are intentional or “top down”, because really a large portion of them are “body up,” informed by our sense of how safe or threatened we are in the moment. If we think all behaviors are being done intentionally, we take them personally, judge them morally, and punish some of them in ways that make things worse. Rather, we need to see them as “body up”, and to work on the conditions for safety and engagement.

When we see that we’re emotional — I mean is this not one of the fundamental qualities of humanity? — we also can tap into the research that says our brains determine how valuable information is (and thus what gets remembered) based on the intensity of emotions encoded alongside it, and to what extent it is used socially. So if you want someone to remember something, create a shared, emotional experience around it. End of story. Why do people remember so little of, say, middle school academics but so much about their friendships or the way one teacher really loved or hated them? Because it’s emotional and social. That’s how we learn.

Here's a quick way to test how we’re doing here, for a middle or high school: how much of the school day is available for (1) physical movement and (2) unstructured social time? If it’s less than a third of their day (not a scientific number, just an estimate), we are probably pushing them off their optimal development path.

3. To create a more vibrant society (or school), use less coercion.

Sneaking in here in the middle is the biggest one, I think, and the one that troubles me most because of how blind I’ve been to it. We are habituated to what in the future may seem like an astonishing degree of control and coercion over our kids and students. We hardly notice when we plan their whole day for them, deprive them of all kinds of freedoms, and generally give them close to zero practice for building a sense of agency. We’re annoyed when as adolescents they start categorically resisting all of our suggestions, even the really good ones, because we think they’re reacting to the idea, when often what they’re really saying is “enough of you controlling everything, I am capable of handling some of my own life now!”

This one hit me hard because I had been congratulating myself on building a project-based school that did, indeed, create much higher engagement for students than typical classrooms. And it’s a great school. But then it hit me that, while for most kids projects are a far more interesting way of learning than lecture-based classrooms, we are still doing projects in ways that are (unnecessarily) coercive. We’re controlling which projects students do, holding them to standards they have no say over, and de facto punishing them for not completing the project when and how we wanted them to. Ouch.

We can do better. We can trust kids, using models like the Sun Model of Youth Co-Agency to give them more control and power. And we have good reason to. There are several research sources pointing to the psychological problems caused when humans don’t feel they have control over their life, and/or don’t have the opportunity to be independent. Most recently, a well-publicized study by Peter Gray et al indicated correlations between declining childhood independence and the increasing rates of depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders in teens. Or to put it more positively: kids will find more well-being when they have meaningful independence and control over their time. Not to mention they’ll be more effective learners, because as we probably know intuitively, when we choose an experience, we care more and access more of our motivation.

4. To unlock human potential, design for our sensitivities.

Factory schools tend to think everyone should be “normal”, which is an arbitrary definition, and people who are different are wrong, worthy of punishment or a label indicating some deficiency. By trying to normalize everyone, they end up destroying a breathtaking amount of human potential. How many kids fit the “normal” definition of a learner who, say, can sit quietly 90% of the day and absorb mostly spoken information, excel in abstract memorization, etc? I’d suggest a generous ballpark figure of 25%. That means 75% of the population not only didn’t get the right conditions to grow, but was probably told more or less that they’re stupid and not as good as others. Check out the amazing book Normal Sucks for a much deeper and also funnier take on all this.

So what can we do differently? Take the things that drive factory schools mad — like the kid who can only think when he’s moving, or the kid who can’t stand the loud chaos of the classroom — and make your education adapt to meet their needs. First you’ll find that not only those kids do better, but many others sort into more optimized learning paths. Then you’ll find that those annoying sensitivities that gummed up the factory works are actually incredible gifts waiting in these individuals. Our sensitivities, even those peculiar ones, are a form of raw intelligence — just waiting to be activated through practice into our greatest contributions. There’s much more on this in a piece called Spinning Straw into Gold.

5. If we got things right in adolescence, it would change everything.

Let me say this bluntly: nearly all of us are traumatized by adolescence. But in ways that are so common that we don’t notice it. The problem is that our society doesn’t really know what to do with adolescents. Instead of helping them, we control them, add immense stress to their lives via school, and for good measure make fun of them for being “hormonal” and surly. Because we generally don’t understand their developmental needs, we end up more or less forcing them to shut down major parts of themselves. Whole categories of human capability are tucked away, even forgotten about. Then later, when we need to raise or teach adolescents, we find ourselves oddly perplexed and triggered by them. It’s because we’re not done yet. We too were adolescents who went through this system and didn’t get fully baked.

What if we saw the presence of adolescents in our lives as a second chance? What if it were an opportunity to return to the confusing but fruitful time of our own adolescence, and re-start our growth? I made the case in A Second Adolescence that this is one of the best chances for growth we’ll get in adult life. Plus, by returning to that uncertain but dynamic ground of inviting personal change, we will discover how to connect with and support the adolescents in our lives.

If we could do this, and design schools that hit those notes in numbers 1-4, then the incredible activation of human potential that is adolescence would go dramatically better. It would still be awkward and confusing — those are markers of rapid growth. But it would be far less traumatizing, and we could enter adulthood knowing our bodies, seeing deeply into our emotions, becoming skillful in our relationships, and holding confidence that we are valuable and good people with a unique set of skills, sensitivities, and passions, able to make a contribution to others that only we can make.

Well, there you have it. It’s not a comprehensive list, but I think it would make a pretty good start. Tap into these five areas and we might just make schools that would unschool themselves — meaning they would start looking so different from the “school” idea in our brains, which is really a factory model, that we would not recognize them as school. They might look more like a café, a community center, or simply a town that is vibrant and connected. Such a place might even look a little like those beautiful images from solarpunk artists, who imagine cities remade with flowing water, verdant paths, and spaces to connect and communicate. Yes, it’s a little utopian. But at the very least, it’s a signpost way out there in the future. Let’s walk in that direction.

In other news…

A Book: If you have a middle schooler or someone approaching that age, or work with early adolescents, I wrote a book for you. Building on idea #1 above, it’s all about understanding adolescent development so we can meet their needs more directly, and help them become the engaged, passionate, curious humans they really are.

A Training Program: There is a secret door in many school schedules, leading to a place where we can transform our practice as educators and offer a priceless gift to middle and high school students. Don’t tell anyone, but….it’s advisory. It’s laying low right now, pretending to be a study hall or boring homeroom time. But advisory could be the time when educators get to exist as something closer to a mentor. Instead of an instructor, to be a facilitator. To create a safe and brave space where adolescents can make sense of their lives, meet their need for belonging, and learn how to manage their inner lives and relationships. Advisory practice is just about my favorite thing in education, and I love and have the privilege to train teachers from all over the world in how to become excellent advisors. We just opened slots for our next training institute, in July 2024 in San Francisco. More here if you’d like to join us.

A Wish: For those celebrating a holiday of some kind in these coming weeks, or at least enjoying a change in pace because of those who are, I wish you a sweet, restful and playful end of 2023! Let’s make 2024 just a little better, a little kinder, a little more solarpunk.

I love this post, especially the part about coercion. When schools in NY were reopening after the COVID shutdowns, I heard a lot of adults worry about how well children would react to being asked to mask, distance, etc. I made the point repeatedly that kids would likely think nothing of it, because they are already so tightly and forcibly controlled while they are at school. What's a few more new restrictions on how their bodies can exist within this space?

There's so much good stuff in this post! I particularly like this: "By trying to normalize everyone, they end up destroying a breathtaking amount of human potential. How many kids fit the 'normal' definition of a learner who, say, can sit quietly 90% of the day and absorb mostly spoken information, excel in abstract memorization, etc? I’d suggest a generous ballpark figure of 25%. That means 75% of the population not only didn’t get the right conditions to grow, but was probably told more or less that they’re stupid and not as good as others."

and

"... our society doesn’t really know what to do with adolescents. Instead of helping them, we control them, add immense stress to their lives via school, and for good measure make fun of them for being 'hormonal' and surly."

That last point particularly stands out to me b/c it's the first time I've really heard/read somebody say that. I've found my sons' adolescence to be extremely challenging -- esp. the 1st go-'round b/c I was pretty much completely unprepared for it and, like you said, had no idea what was developmentally appropriate. And b/c I hadn't dealt w so much of *my stuff. As they've grown and I've grown, I've learned that adolescence -- their experience of it AND my experience of it -- is easier, more pleasant, and more fulfilling if I give them space, allow them to take on and tackle challenges of their choosing, and facilitate/support their endeavors as I'm able (and within reason).